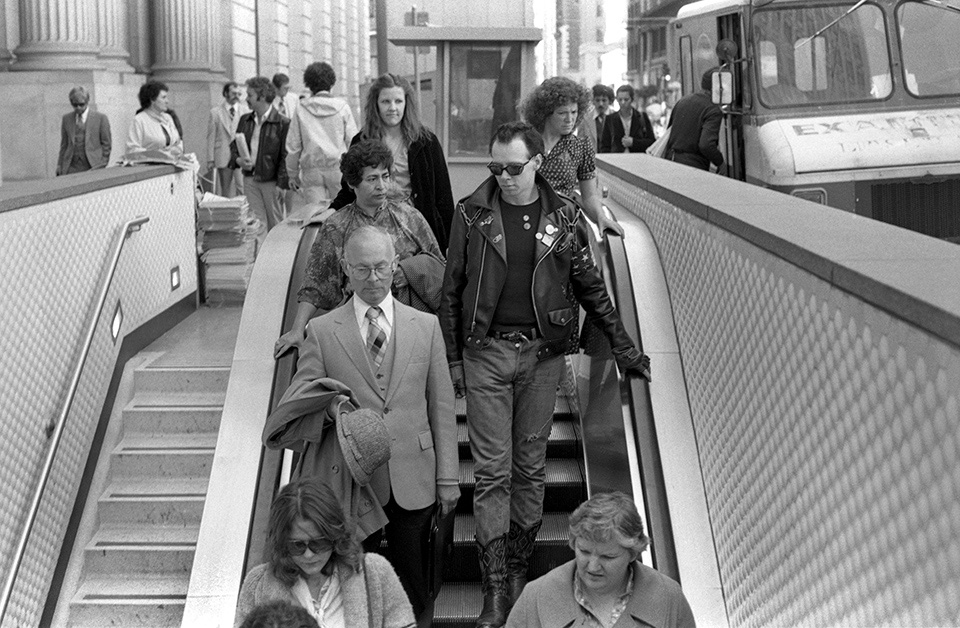

1980s Punk San Francisco: Photographs by Jeanne Hansen

Interviews and introduction by Jonah Raskin

This online exhibit features a sample of the 16 interviews and over 40 photographs that will be on view in the exhibit Alternative Voices in the Main Library's Jewett Gallery — opening date October 9, 2021.

You can explore the venues featured in this exhibit on Google Maps, where you can find more information about each venue along with links and photos.

George Moscone and Harvey Milk were dead. Diane Feinstein sat in the mayor’s office and insisted that San Francisco wasn’t “the kook capital of the world.” Normal is what she craved—exactly what the so-called kooks were running from, whether they came from New York, Florida, Texas or beyond.

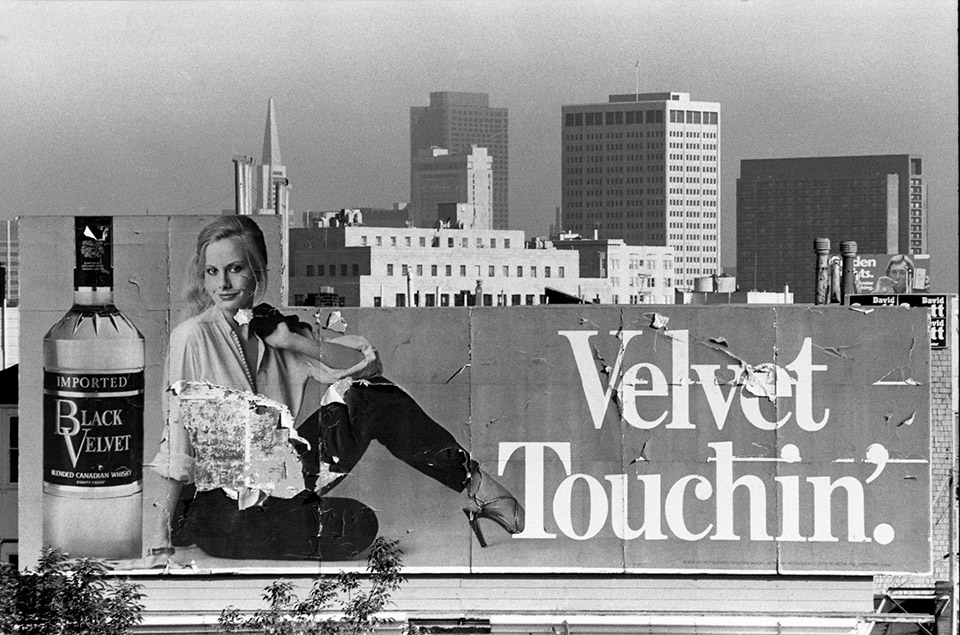

In the 1980s, San Francisco grew blander, wealthier and more corporate almost by the day, but a resilient multi-cultural underground thrived in nooks and crannies. Punk rockers and their ilk boasted their own music, zines and newspapers. In galleries, clubs and back alleys they created their own forms of artistic expression that spread to nearly every neighborhood in the city, though news of the subterranean world rarely made its way into Herb Caen’s columns or page one of The Chronicle.

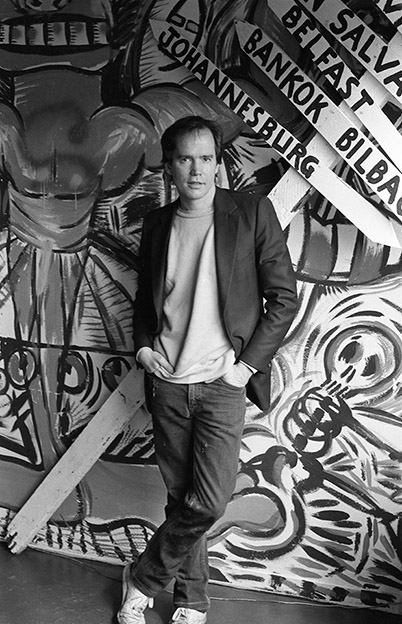

With sharp eyes, attentive ears and a big heart, photographer Jeanne M. Hansen lived and worked in the center of the San Francisco underground. She had moved to the city in 1980, to study at the San Francisco Art Institute. Quickly, she dove headfirst into the subterranean vortex that existed apart from North Beach and Beat Generation enclaves.

Today, Hansen says, “The Mission District, where I lived, attracted scores of artists and musicians who moved into neglected storefronts, cheap apartments and abandoned buildings—and recreated Bohemia.” She became an integral part of that world and also stood out from the often male-centric crowd. Inspired by women who broke boundaries, she used her camera as a means of liberation.

In the 1980s, before I met Hansen, I lived in Sonoma County, though I often visited San Francisco to witness the genesis and evolution of its underground cultures. Now, gazing at Hansen’s photos and listening to the voices of the people featured in this exhibit, I experience the era all over again.

Most of the artists and performers Hansen photographed didn’t become superstars, though some had fifteen minutes of fame. They came from different places, backgrounds and kinds of families, and, in San Francisco, they coalesced to create a D.I.Y. culture that sustained them through the 1980s and beyond. In the act of rebelling and storytelling with uncommon words and images, they reinvented San Francisco as a destination for young people who rejected the America of Ronald and Nancy Reagan, Tom Cruise and Anita Bryant, and sought the authentic, raw and lyrical.

Hansen’s photographs feature a cast of unusual characters you will meet on the walls of this gallery. Forty and more years after the interview subjects in this exhibit defined the punk era and stamped their image on the city, all but one are alive today. Their voices make up a chorus that accompanies Hansen’s photos and express the soul of a city that to a large extent no longer exists, except in the lingering melodies of the era, and in the hearts and minds of the survivors.

“By taking pictures and trusting my instincts, I documented a vital part of our city,” Hansen says. “We have a rich tradition of countercultures that one can still find if one looks in the shadows of the skyscrapers, office buildings and corporate headquarters.”

Foremost Warehouse, 1980

Stannous Flouride

My real name, from birth, is Kevin Kearney. Now, as a local historian I lead Haight-Ashbury walking tours. Stannous Flouride is my alias. Back in the 1970s, my girlfriend and I were on our way to the organizational meeting of Rock Against Racism and we were making up punk names. At the meeting, I signed in as Stan S. Flouride. Later I realized I misspelled Fluoride. “It’s just a name,” I said, and stuck with it. Jello Biafra told me, “Stan, you’ve got to meet my new bass player, Klaus Flouride.” I replied, “Ah, my long-lost brother!” For years Klaus and I said we were identical twins, but didn’t look the same because daddy worked at Los Alamos.

I grew up in New Jersey, got involved in radical politics in Washington D.C. and in 1972 was drafted. I felt there was nothing inherently wrong with the military, and that as long as I didn’t get an order I couldn’t obey, military life would be okay.

When I came to California I lived in the Haight, which collapsed after the Summer of Love. The rebirth came mostly from young, gay, hippie men who couldn’t afford the rents in the Castro, so they came to the Haight, where it was affordable. In 1973, two guys who collected porcelain and were members of the Radical Faeries opened Dish, a pagan gay collective. You can’t get more San Francisco than that!

When I saw my first punk show I was working at a café with Bruce Loose from Flipper, and acting and dressing like a metrosexual. Bruce bought me a ticket for the Sex Pistols at Winterland, which was my initiation. I was glad to see rebellion in music, which had been missing for almost a decade. For me punk was about an anarchist revolution and no leaders.

I worked the doors at the Deaf Club and Target Video, and mastered a look that told idiots I’d kick their ass if I had to, though I mostly made a name for myself not as a bouncer but rather by writing six episodes of “City Tales” for Damage magazine, a punk version of Armistead Maupin’s column “Tales of the City.” I did speed so I could stay awake and make art, but quit when I got bored with myself and the people around me.

I was part of the Suicide Club, an early expression of urban spelunkers, who went on outings at the abandoned National Guard Armory at 15th and Mission and at the Hamm’s Brewery at 16th and Potrero. Someone got ahold of a jackhammer, which we used to take out the doors and open holes in the giant tanks and make living spaces. Punks moved in and squatted. It became known as “The Vats.”

I also worked, first at The Acme Café and at the Church Street Station, which was a gay Denny’s. For five years I was a waiter on Haight Street. I waited once on Baba Ram Dass, walked up to him and said, “Are you who I think you are?” He said, “More importantly, are you who you think you are?”

Valencia Tool & Die, 974 Valencia Street, 1983

Mia Simmans

My first great love, Bruno, looked at me one morning and said, “You look like a frightwig.” I was 18 and he was 30. The name just stuck. Male privilege was less contained in those days. It was just part and parcel of being a young woman in the early 80s that men were going to aggress you. As a teenager on the streets of San Francisco, I was hassled a lot and felt angry. My big thing was to look good from the back and super scary from the front, to scare them away because they scared me.

Deanna and I were drawn to one another; we met at a movie theater where we worked. It was just one of those magic things when you meet your soul mate. But we also had a lot of angry shows. That’s like a lot of relationships: you get mad at each other, you go through all of everything. And that’s what makes a relationship. You know, the thing with Deanna and me goes so deep, deeper than the music. Like we play music together because that’s what we do. We could be playing bridge or putting a puzzle together, but the thing we do together is make music. We make up songs from nothing and we work well together.

We did a lot of touring, loved it—literally, jump in the car, drive to New York, and then figure it out from there. We got to the 8BC Club in New York, which became one of our homes. I’m of the basic belief that if you are getting up on the stage, you have to give people something interesting to look at. It’s part of the deal. We did thrift shopping, got up on stage in costume and guys would say, “Show us your tits or else get off the fucking stage, blah blah.” We’d turned it around and said, “Show us your dicks, then, you know, come up here and strip.”

At 16, I moved to San Francisco on my own steam. I got a really good [music] education from my hippie mom, you know, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Joan Baez, Jimi Hendrix and the Beatles. I am grateful to this day that I was exposed to so much good 60s and 70s music. Now, the world is so clearly rigged that there’s going to be three people with all the money. They’re going to control the food chain, and it’s not going to be equitable. Still, we want to do the soundtrack to the revolution.

In the 80s we could work our crappy little jobs and get minimum wage, which was, I remember, $3.25 an hour at the Egyptian and the Strand on Market Street. Our studio was opposite the Sound of Music; we had to carry our equipment at three a.m. downstairs in spiked heel shoes and really blotto drunk.

Now, writing lyrics is my favorite thing to do. I’m compelled to write. I feel like all the words belong to me. What Deanna and I have together, our friendship, our sisterhood, whatever happens with Frightwig, we’re going to be tight and deep forever.

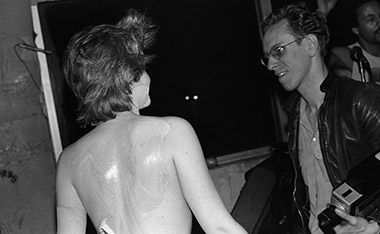

Great American Music Hall, 1986

Esmerelda

When Mayor Moscone and Supervisor Milk were assassinated it was the end of our San Francisco. The San Francisco Chronicle had been the hub. Everyone knew what was going on in our town. We had Herb Caen and we loved our city.

After Dan White’s acquittal there was devastating depression and indulgence. Persian heroin flooded into the city with the fall of the Shah and everybody was “chasing the dragon.” Battling alcoholism on New Year’s Eve 1979, I had a vision. An Angel appeared: “You will soon be needed—you must become clear.” So I moved to the country and got sober.

In sobriety, songs downloaded in my mind daily. I’d have to pull over to the side of the road to write them down. I’m from in L.A. but my dad was from the Dust Bowl in Texas. I grew up with Jimmie Rodgers and Hank Williams. Always loved the minor keys. At 16 we crawled the Sunset Strip clubs to see The Doors, The Seeds, Love. Extremely religious, I discovered The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Siddhartha, Alan Watts and taking acid.

I dropped out of high school, ran away to the Haight and was soon in the front row at all three days of the Monterey Pop Festival on acid! During the Summer of Love we drove a psychedelic painted hearse across the country, selling acid on college campuses. When we returned the Haight fell apart. I moved to Marin and lived with an all-girl rock band called the Ace of Cups. Then Neal Cassady died so I hitchhiked to his wake in Big Sur, where I met my husband and soon after had my children. The marriage ended as Comet Kouhoutek came to Earth in 1973. At a festival in S.F. I met the Angels of Light: genius hippie drag queens, pretty girls and babies all covered in glitter. I found my tribe and sang in their free shows.

Angel Gregory went to London and discovered punk and brought it home to us in ‘77. Overnight we cut our hair and became punks. Angel Steven Brown started Tuxedomoon while me and drummer Tony Hotel launched our band On The Rag (Noh Mercy). The Mabuhay and Deaf Club were our stages. We lived in the old Cockettes storefront at 992 Valencia Street. No one worked. We just played.

In the 80s I performed solo “post-punk cabaret” with taped synthesizer at all the great S.F. clubs like I-Beam and Club Nine, and in New York clubs like Danceteria. (I was headlining while teenage Madonna was in the basement taking notes!)

When my friend musician Patrick Cowley died of AIDS in 1981, I finally realized the vision of 1979. Because I was now “clear” I was able to help others when so many friends continued dying of the plague. Although terrifyingly horrific, the 80s had the best creative fashion and amazingly joyful dance music (before the accountants ate the music industry).

In 2000 I had a realization that “Service is the Artform of the 21st century.” Wishing to help others, I changed my aspiration and began working in a green cemetery.

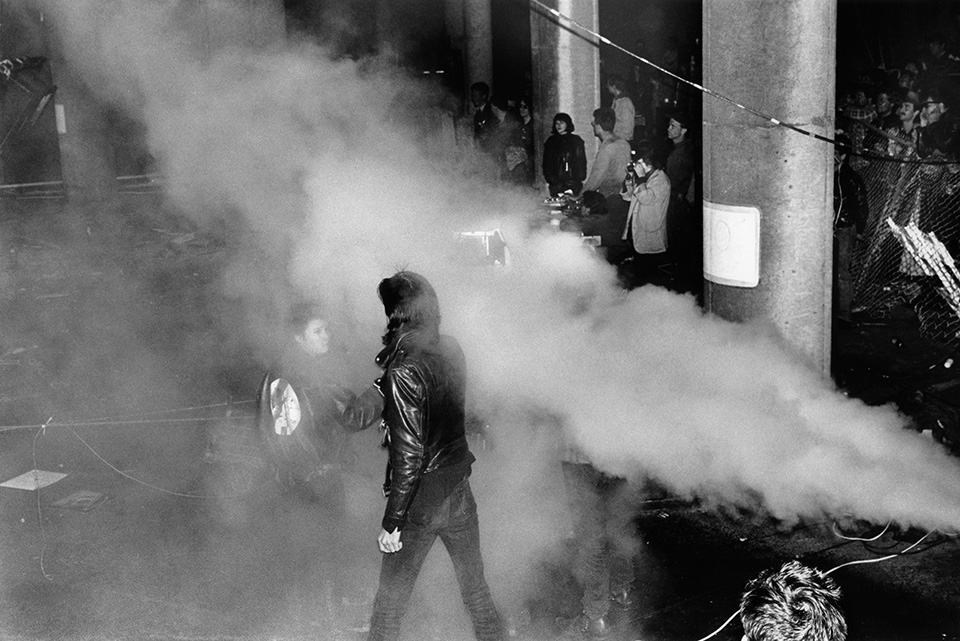

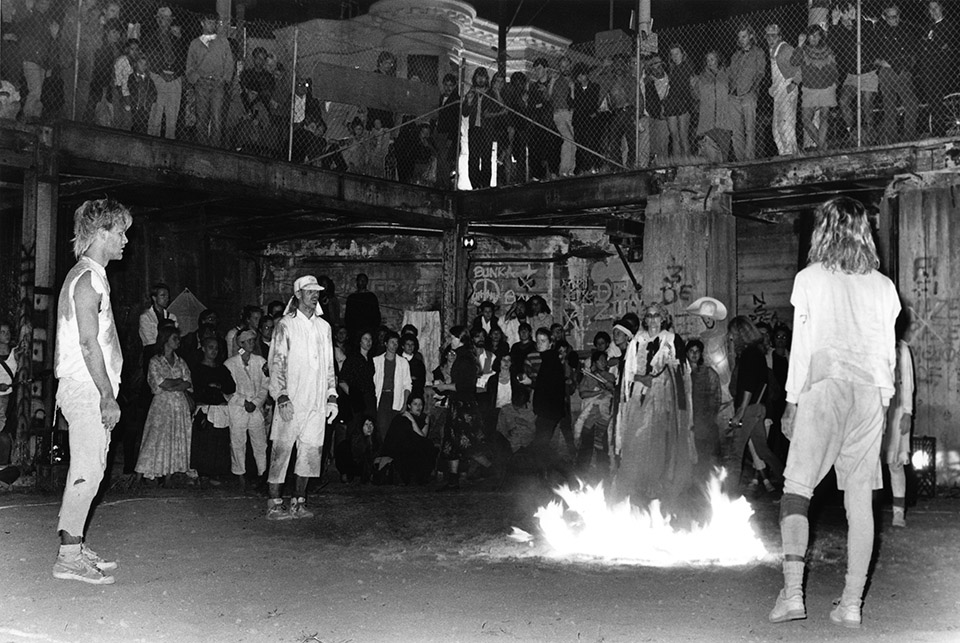

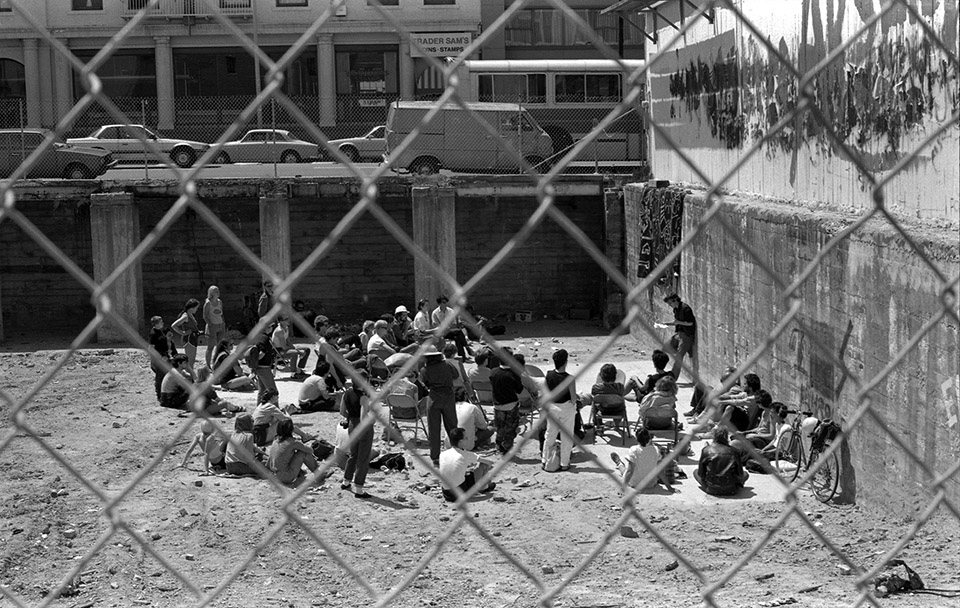

Gartland Pit, 1986

Keith Hennessy

I went to school in Montreal, where I had a taste of class-based politics and feminist organizing. I hitchhiked to S.F., showed up, like thousands of others, a lost kid with no money and juggling clubs in my backpack. I lived off being a street performer, doing acrobatics and political comedy. The people I ran with were punks with hippie values trying to prevent nuclear war and stop the spread of nuclear power.

Politically speaking, I grew up in San Francisco in the Eighties, a time when there was a network of collective and anarchist houses that had a spiritual component, though there were also tensions between arty and political anarchists. White people were looking at their own histories, which led them to pagan rituals, some of which we adopted. We had a band called “Group Rhythm Therapy.” It could be five to twelve people. We gave audience members percussion instruments, pots, pans and sticks and played for twenty to thirty minutes.

My first original solo piece, “Saliva,” marked the beginning of my career. The setting was beneath a freeway, south of Market, where I negotiated a space with the homeless people living there.

Before that I was with Sara Shelton Mann’s experimental group, “Contraband,” which fused anarchist street politics with improvisational dance and that broke down many of the gender roles that define classical ballet.

A decade after a suspicious 1975 fire burned down the Gartland Apartments on the corner of 16th and Valencia, Contraband performed a piece called “Religare.” The space was dubbed “The Gartland Pit.” The Urban Rats publicized it with their “landlord arson” murals. Twelve people died. We had to do major clean up because people who were shooting up used it. Religare was created “site-specific” for The Pit. It was a ritual, a dance performance and a live installation that involved the audience and that told much of the story of the fire and its aftermath. Now, in that space there’s affordable housing and a social activist coffee house.

Back then, we complained that we missed the cheap rent of the 70s, but looking back, it’s like we were the last generation to enjoy it. There is still a Latinx community and political organizations in S.F., but we have lost much of the city. We didn’t start restaurants in the Mission. We went to Mexican places, had a $5 burrito and were happy to eat a good meal. The potluck, which was foundational to lesbian, queer and left culture, still exists, but they’re less frequent. Each individual has his or her own diet.

Still, the spirit of the anarchist, spiritual world of the Eighties survives. I live in the Pigeon Palace, a community land trust house, which we bought with public funds and which is owned by the non-profit San Francisco Community Land Trust. My work is engaged with social justice and antiracism.

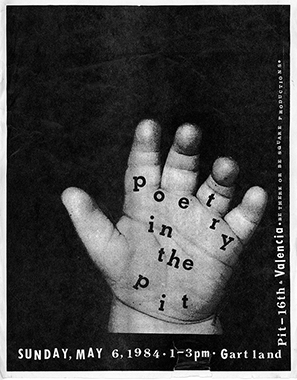

Flyer art by Dana Smith, 1984

Dana Smith

I was born in Staten Island, New York, and grew up in Denver, Colorado. At 18 I moved to Portland, Oregon, where I lived for five years, and in 1982 when I was 23 moved to San Francisco. As a child, I was against the Vietnam War, but my family was apolitical. I started making art seriously in high school and then studied art for four years and got a BFA. For about a year I traveled in India with Giti Thadani, a lesbian and feminist who taught me about ancient Hindu art.

In 1989, I went to the San Francisco Art Institute for a master’s degree in painting. Away from my family, I began to move in progressive and radical circles and was really attracted to punk and the punk anarchist scene. I loved the loudest punk shows, slam dancing and Rock Against Reagan, Rock Against Rent, rock against whatever you got. In 1984, I protested at the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco.

I loved Patti Smith and I loved powerful women artists like Susan Cervantes and Juana Alicia Montoya who created wonderful murals and helped generate multiculturalism in the arts, which really caught on. From my twenties to my forties, I did a lot of graphic design and joined North Mission News, where I met Peter Plate, got a black leather jacket and threw myself into guerrilla street installations, though I never sat down in the street, locked arms and was arrested. Peter was a big influence.

When Dianne Feinstein was running for mayor, some friends and I did a poster that read “Re-elect Frankenstein” that showed her with a “Bride of Frankenstein” hairdo. In the night we plastered her headquarters. Herb Caen loved it. Another time, we blocked Maiden Lane, put up signs that read, “Danger, PCBs,” with images of skulls, and poured white powder everywhere. We also addressed the issue of tenants’ rights with street theater, though the really big issues for me in the Reagan years had to do with the Contras and the Sandinistas. Those issues expanded my awareness of international politics. Older Nicaraguans came to the Mission, and in a sense, the war continued here. Dolores Huerta from the Farm Workers always showed up and inspired me as well as others.

Around this time I became a squatter. We changed the locks on our building, called PG&E and they got everything up and running. The same happened with the phone company. For five years, I worked at Rainbow Grocery and that was also part of my education, especially when the organic guidelines were developed. There are so many wonderful continuities and connections, though there was also the dark side of San Francisco in the 1980s, including heroin and cocaine, which I didn’t do. I was always a pothead and I always felt that I loved people. I still do. I love people, though the saddest thing is that a lot of people I loved died of AIDS.

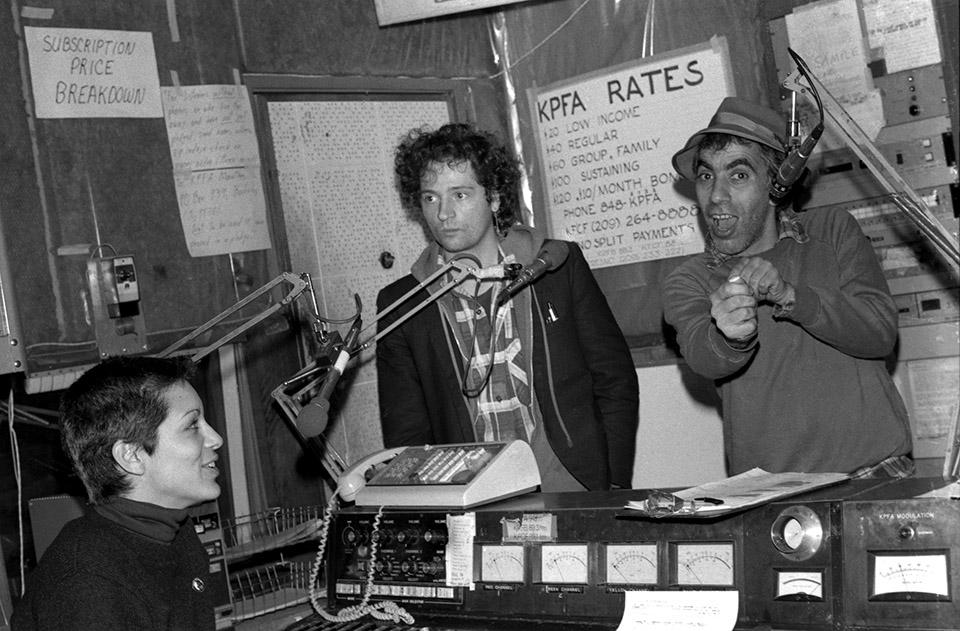

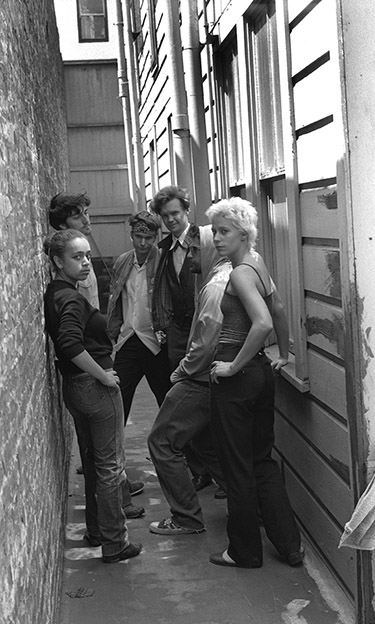

Christa, Joe Gore, Swack (Pete Scaturro), Robin Banks

(Robin Balliger), Roberto “Bo” Razón, 1986

Robin Balliger

The punk moment was an incredible outpouring of politics and creativity. The poet Rocket and I started the band the Appliances by making noise in the basement of Mary Kelly, the guitarist and composer for the Contractions. Rocket was great at making things with amplified bongs, weird strings and kitchen appliances, which is where the name of the band, the Appliances, came from.

I’m from San Diego, born in 1958, so I lived through the nuclear threat, the assassinations and the War in Vietnam. We sat around every night in the living room and watched the news about Vietnam and the body counts. I belong to a generation that felt like we could be annihilated at any moment, like somebody was going to lean on the button and that was going to be it.

I went to the Naropa Institute in Colorado in the summer of 1976, during the Bicentennial. As soon as I got back to San Diego, I knew I had to get the hell out of there. I transferred to UC Berkeley and moved up there in 1977, graduating with a music degree in 1979.

When the punk scene first started, it meant everything from three-chord hardcore bands to the most experimental performance art and everything in between. There was also a lot of crossover with black music and hip-hop. That’s missing from the history.

There was this guy named Zev, who was a performance artist who strung plastic bottles together and did this performance of smashing them on the stage. But it was also dance. Stuff like that was just happening constantly.

When I first heard the Sex Pistols I was blown away. I had never heard rock before that was so political and overnight I became a punk! But focusing on just eight performers like Johnny Rotten isn’t true to the energy of that moment, when San Francisco felt like the Mecca for consciousness, activism and the counterculture. I probably saw The Dead Kennedys fifty times. I’m not kidding. I remember Jello Biafra got his pants ripped off. Oh god, the good old days!

Also, there has never been a moment in popular music where women felt so empowered. Another thread is the whole gay movement, which was also extremely important, and which was multi-racial and fused the dance and club scenes.

At Komotion, people from all over the world played music. It was amazing, considering it was pre–social media and it lasted for ten years. To do some of the shows with international artists we had to advertise and so the police were more aware of the space. We cut back on promotion, and then did more local punk shows.

I remember the 1980s fondly because of punk, but punk became mainstream and the whole mosh pit thing got more aggressive and then it was only guys. The 1980s were an oppressive era that saw the destruction of labor and the rise of privatization, globalization and deindustrialization: all that stuff which we are living now. In 1998, I moved to West Oakland; there were abandoned buildings, drugs and guns. The last band I was in was Afro-Peruvian. We hardly ever performed, but I enjoyed playing the music.

dinner for Queen of England, Golden Gate Park, 1983

Club Generic Underground, 1983

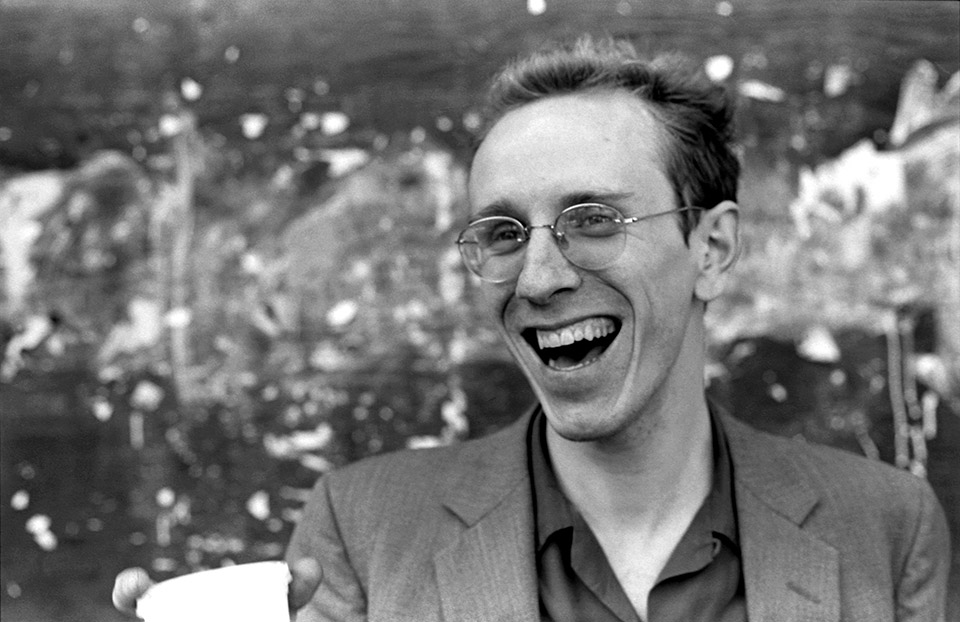

Stephen Parr, 1953–2017

I grew up in Syracuse, New York, where I had a place called Café Bazar and another called the Performance Gallery. In Buffalo, I spent days with Julian Beck and Judith Malina of the Living Theater, which changed my concepts of acting and the stage, and I read a lot of Artaud, which altered my ideas about performance. Also, I was influenced by Nam June Paik, John Cage and Emmett Grogan. That might sound pretentious, but it was true for me.

I was never interested in the conventional ways of doing things. So I moved from the East Coast to San Francisco, oddly enough, right after the assassinations of George Moscone and Harvey Milk. My goal was to create art, whether it was working with sound, video, cinema or curating events and making things happen. A lot of other people, for whom San Francisco was a wide-open place, wanted to do the same and similar things. San Francisco has always had a history of experimentation and a literary culture.

The movements of the 1980s, whatever you want to call them—punk, or new wave—drew on that tradition. At the Club Generic, which I helped to create, the only rule was that you couldn’t die. Also, there were people I would not allow in the bathroom for more than a few minutes because that’s where they did drugs. I had very little interest in drugs. All over the city, there was a high degree of experimentation, collaboration and a feeling that things were changing, moving someplace, and giving people a sense that things weren’t static. It wasn’t so much about what was created, but rather the creative process itself.

Every week there would be a new thing: a guy who swallowed chairs; and a guy with one arm who played the didgeridoo. I had another place called New Generic that lasted about a year, and after that, I moved to Gray Street, where I published small press books and had a salon where I showed artists like Su Chen Hung, Scott Williams and Gavin Flint. The SFPD raided it, so I started a nightclub at Hunter’s Point to take the scene out of the city center into more of a netherland.

Back then, few of us made money or got paid. Money was not the impetus and it wasn’t remotely like Facebook. Today, we’ve gotten a lot more narcissistic and self-congratulatory. In certain ways, we’re also more astute, because we’ve seen so many different things, but a lot of people haven’t been able to contextualize those things or put them together in a way that’s really benefiting anyone other than themselves or their own brand.

For years, we screened movies here at Oddball Films, which was also an archive. People would tell me, “Oh this is great stuff.” I’d say, “It’s shabby stuff, but it has a certain charm and truth to it. That’s what really resonates. You know, there’s very little great art.”

Tara Ford on Stephen Parr:

I performed at the Mabuhay Gardens and Tool and Die, but always my favorite place to perform was Club Generic because I could do whatever the hell I wanted. The beauty of Club Generic was that artists were really free to do uncensored stuff. People who did shows in other places, when they came to the Generic, they would create a different level of work that was almost automatically what you might call “political.” It really addressed issues that weren’t going to be addressed if they went to the Mabuhay. In one of my performances, I wore a pair of ragged men’s underwear and wielded a meat cleaver.

Stephen Parr was there at Club Generic to provide some structure and some support. As long as you had a show that was somewhat entertaining you could perform it. If you weren’t entertaining, he’d get the hook and get you out. What most of us artists soon realized about Stephen was his mission, which was to create and recreate himself. He always had a great artist heart.

San Francisco Public Library Historical Photograph Collection)

Mark Rennie

One of the hardest things I ever did was breaking away from the East, because the East has a consciousness all its own. I grew up in Columbus, Ohio, and my mother said, “Get out of here. Go to California.” When I came to San Francisco it was before the microprocessor and Silicon Valley. It was the edge of the universe. I was young and kind of wild and punky. I went to Hastings, became a lawyer and thought of the law as theater. I saw opportunities and always had rules. Number one pay attention, two speak the truth, three ask for what you want, four keep agreements, and five take responsibility for everything that happens in your world.

I put deals together, put nightclubs together, put restaurants together. My attitude has always been, trust the universe to provide. I have had deals where I just took a dive into the void. Failure is not an option. We did Club Nine where the whole idea was to be a crazy art bar. We would have a theme for six weeks and then we would change it. Tony Labat was our opening act. Also we started a company called SOMA Development. We ended up with fifteen buildings south of Market where we created bootleg artists’ lofts.

We would take a big building and we’d bust it up into, you know, 2,000 or 1,500 square foot units and we’d rent them out 15% under market. One of the buildings was on the corner of Ninth and Folsom, which became The Billboard Café. Upstairs we called The Clown Hotel. We found out that Ninth Street was the second busiest street in San Francisco because two freeways came together. We had a full-on facade so we started hanging canvasses. We would have a painting up and make some cheeky comment and get on television. It was all about getting the media’s eyeballs and telling a story. Our biggest fans were the media.

We had the hottest restaurant in town and I said isn’t it weird because we’ve been pretty good artists and had a reputation, and no one gave a shit, but if you have the hottest restaurant in town, you’re a superstar in San Francisco. The problem with the restaurant business is that you don’t make any money.

Then there was Jonestown and Milk and Moscone assassinated and AIDS. There was evil in this town as thick as tar. You could cut it with a knife. Everybody forgets that Jonestown happened right before the assassinations. People were so in bed with Jim Jones it wasn’t funny. If you wanted to have 500 people picketing City Hall, Jones could get them there in 15 minutes.

After ’87, Club Nine, where I was the impresario, shut down because of a noise problem. The house band was Chris Isaak. The coat check girl was Courtney Love. I wish I still had the T-shirt that said, “Intelligence is the Ultimate Aphrodisiac.”

About the photographer: Jeanne M. Hansen

Jeanne M. Hansen bought her first camera at age ten with money earned from picking strawberries in Skagit Valley, Washington, where she was born and raised. Trained at the Brooks Institute of Photography in Santa Barbara for a year, she transferred to San Francisco Art Institute and received a B.F.A. in Photography. In 1990, after a decade in San Francisco, she returned to Skagit where, as a single mother, she raised her son. Her work has been exhibited in galleries, museums and public spaces. It's also in private collections. Hansen contributed to the award-winning book and exhibit Harvesting the Light, which advocates for the preservation of farmland. In Bellingham, Washington, she worked at a photo lab and the Whatcom Museum of History and Art, specializing in black-and-white printing. In 2013 she returned to San Francisco to work on a multimedia project about the alternative art, music and political scene during the punk heyday of the 1980s. Visit Jeanne M. Hansen’s website at www.jeannemhansen.com.

About the interviewer: Jonah Raskin

Jonah Raskin, a novelist, biographer and performance poet, has lived in Sonoma County since 1976. An ex-New Yorker, he was educated at Columbia College and The University of Manchester, England, where he received his Ph.D. A long-time book reviewer for the Chronicle, he has written about San Francisco history and culture, Jack London, the Beats and the upheavals of the twenty-first century.

Acknowledgements

Jeanne M. Hansen: I would like to thank Ken Tray, my husband, for being with me on this journey; Miguel Carlos-Hansen, my son and fellow artist; Carl S. Hansen, my Dad, for always believing in me; Marsha Tray, my mother-in-law, for unending inspiration; Jonah Raskin, my partner in this project, for showing me the value of a story well told; and Judith Walgren, Associate Director, Michigan State University School of Journalism, for providing invaluable editing with another set of eyes on the contact sheets. And I also want to give a warm thank-you to everyone who sat down to share their stories for the interviews.

Jonah Raskin: I would like to thank my brothers Daniel and Adam Raskin and my sister-in-law Adelina Aramburo.

Additional thanks to: